Tag Archives: dítě

Jak to bylo s králíky

Médii rezonují výroky papeže Františka o králících a o tom, že tři děti stačí či že jsou ideál. Nevím, jde-li zde o hloupost dotyčných redaktorů, či o jejich zlý úmysl, každopádně by si měli dát studený obklad. Páč ačkoliv se papež zrovna nevyznamenal, takové blbosti a nehoráznosti, které mu novináři vkládají do úst, ve skutečnosti vůbec neřekl…

V prvé řadě: papež ve skutečnosti ani nenaznačil, že by tři děti byly dost. Pouze v reakci na otázku, zda tři děti nejsou moc, odpověděl upozorněním, že menší počet dětí vede k extrému vymírajícího národa, takže fakticky řekl, že (v průměru) tři děti na rodinu jsou MINIMUM.

I think the number of 3 (children) per family that you mentioned, it is the one experts say is important to keep the population going,. three per couple. When it goes below this, the other extreme happens, like what is happing in Italy. I have heard, I do not know if it is true, that in 2024 there will be no money to pay pensioners (because of) the fall in population.

Novináři, co celou věc interpretovali jako tvrzení, že „katolíci mají mít jen tři děti a ne se množit jako králíci“, by měli okamžitě skončit, protože jsou buďto blázni, nebo patologičtí lháři.

A teď k těm králíkům. Papež v rámci odpovědi, v níž mluvil o Pavlu VI. a jeho pojetí „odpovědného manželství“, mimo jiné řekl:

Rodičky potřebují empatii, ne zákaz porodů doma!

Svobodův hon na matky domorodičky mi silně připomíná Chládkův hon na homeschoolery. V obou případech si dotyční, mající na své straně majoritu obyvatelstva, vyšlápli na menšinu, která odmítá státní monopol na životy svých dětí. V obou případech jde o témata zasahující téměř každého člověka. A v obou případech se užívá spíše emocí a diskusních faulů, než racionální argumentace. Asi neexistuje lepší důkaz pro toto tvrzení než skutečnost, že Bohuslav Svoboda si na podporu svého návrhu na zákaz domácích porodů „vypůjčil“ článek z iDNES týkající se „domácího porodu“, který vyšetřuje policie pro důvodné podezření (matka nechodila na kontroly, těhotenství tajila), že se jednalo o vraždu. Tedy opravdu „typický domácí porod“…

Přitom by stačilo méně hysterie a více pochopení. Napadá mě paralela s jedním Halíkovým vyjádřením (já cituju Halíka!) směrem k bojovným ateistům: „Bůh, tak jak si jej představujete, opravdu neexistuje.“ To samé, obávám se, vzniklo v případě boje proti domácím porodům. Vznikla představa typické domorodičky, proti které se dá bojovat a nepotřebujeme k tomu ani pochopení, ani argumenty. Studentka filosofické fakulty (či jiného humanitního oboru), neholená primitivka, oděna v batikovanou sukni, živící se klíčky a odmítající očkování, která doma rodí z nejrůznějších poetických důvodů, které jsou tak pitomé, že ani nemá cenu snažit se s nimi polemizovat.

Eugenics and other Evils (1): What is Eugenics?

To the Reader

I publish these essays at the present time for a particular reason connected with the present situation; a reason which I should like briefly to emphasize and make clear.

Though most of the conclusions, especially towards the end, are conceived with reference to recent events, the actual bulk of preliminary notes about the science of Eugenics were written before the war. It was a time when this theme was the topic of the hour; when eugenic babies — not visibly very distinguishable from other babies — sprawled all over the illustrated papers; when the evolutionary fancy of Nietzsche was the new cry among the intellectuals; and when Mr. Bernard Shaw and others were considering the idea that to breed a man like a cart-horse was the true way to attain that higher civilization, of intellectual magnanimity and sympathetic insight, which may be found in cart-horses. It may therefore appear that I took the opinion too controversially, and it seems to me that I some times took it too seriously. But the criticism of Eugenics soon expanded of itself into a more general criticism of a modern craze for scientific officialism and strict social organization.

And then the hour came when I felt, not without relief, that I might well fling all my notes into the fire. The fire was a very big one, and was burning up bigger things than such pedantic quackeries. And, anyhow, the issue itself was being settled in a very different style. Scientific officialism and organization in the State which had specialized in them, had gone to war with the older culture of Christendom. Either Prussianism would win and the protest would be hopeless, or Prussianism would lose and the protest would be needless. As the war advanced from poison gas to piracy against neutrals, it grew more and more plain that the scientifically organized State was not increasing in popularity. Whatever happened, no Englishmen would ever again go nosing round the stinks of that low laboratory. So I thought all I had written irrelevant, and put it out of my mind.

I am greatly grieved to say that it is not irrelevant. It has gradually grown apparent, to my astounded gaze, that the ruling classes in England are still proceeding on the assumption that Prussia is a pattern for the whole world. If parts of my book are nearly nine years old most of their principles and proceedings are a great deal older. They can offer us nothing but the same stuffy science, the same bullying bureaucracy and the same terrorism by tenth-rate professors that have led the German Empire to its recent conspicuous triumph. For that reason, three years after the war with Prussia, I collect and publish these papers.

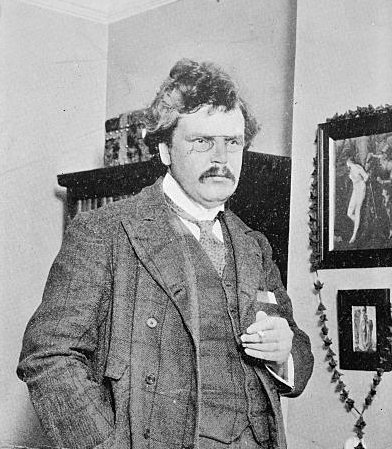

G. K. C.