Tag Archives: šílenství

Tyranský stát

Kázání P. Konráda zu Lowenstein, FSSP

Když se Ježíš přiblížil k městu a spatřil je, zaplakal nad ním. (Lk 19,41)

Scéna první

Pozdvižení v ulicích, nejapné, brutální veselí, alkohol a nepořádek. Co se to tu slaví? Občanský masakr. Kdepak to jsme, drazí věřící? Ve Francii roku 1789 za vlády teroru, kde revolucionáři vraždí šlechtu a zvedají do vzduchu játra kněžny de Lamballe nabodnutá na kopí? Nikoli, jsme v ulicích Dublinu roku 2018. Ráchel neoplakává své děti, protože jich není; naopak, lůza se raduje, protože jich není: oslavuje „dekriminalizaci“ potratu. Dlouhé slovo. Kultivované slovo vzdělaných lidí. Už méně kultivovaná je skutečnost, která je za ním: vražda nevinného dítěte. Avšak jestli to už není zločin, co je potom ještě zločinem? Není-li to zločin, co to potom je? Prý „zdravotní péče“. A co když si dítě tuto péči nepřeje? Smůla. Postarají se o něj tak jako tak. Nemá žádný hlas, žádný nárok vyjádřit svůj názor, žádné hlasovací právo. Když bude křičet, stát ho neuslyší.

Když před několika měsíci někteří naši odolnější farníci stáli u cesty s transparenty hájícími život, byla reakce veřejnosti smíšená. Jeden pán si přečetl „nezabíjejte děti“ a káravě pohrozil prstem. Kdyby byl neprošel kolem tak rychle, bylo by možné se ho zeptat: „Dobrý den, pane, mohu se vás na něco zeptat? Byl jste někdy dítětem? Nebo jste přišel na svět už dospělý jako Adam? Nebo jste jako nějaké mytologické božstvo vyskočil plně zformovaný z Diova stehna? Pokud jste však někdy byl dítětem, nezdá se, že byste litoval, že jste se dožil dneška.“

Ostří si jazyk jako meč, vrhají jedovatá slova jako šípy, aby z úkrytu zasáhli nevinného, aby ho náhle zasáhli, bez ohledu. Rozhodli se pro hanebný plán, smlouvají se, jak by skryli své nástrahy, říkají si: „Kdo nás uzří?“ (Žalm 63).

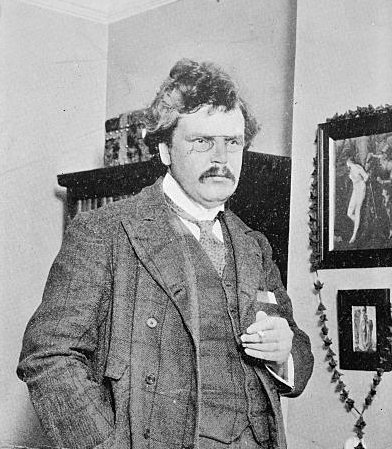

Eugenics and other Evils (4): The Lunatic and the Law

The modern evil, we have said, greatly turns on this: that people do not see that the exception proves the rule. Thus it may or may not be right to kill a murderer; but it can only conceivably be right to kill a murderer because it is wrong to kill a man. If the hangman, having got his hand in, proceeded to hang friends and relatives to his taste and fancy, he would (intellectually) unhang the first man, though the first man might not think so. Or thus again, if you say an insane man is irresponsible, you imply that a sane man is responsible. He is responsible for the insane man. And the attempt of the Eugenists and other fatalists to treat all men as irresponsible is the largest and flattest folly in philosophy. The Eugenist has to treat everybody, including himself, as an exception to a rule that isn’t there.

The Eugenists, as a first move, have extended the frontiers of the lunatic asylum; let us take this as our definite starting point, and ask ourselves what lunacy is, and what is its fundamental relation to human society. Now that raw juvenile scepticism that clogs all thought with catchwords may often be heard to remark that the mad are only the minority, the sane only the majority. There is a neat exactitude about such people’s nonsense; they seem to miss the point by magic. The mad are not a minority because they are not a corporate body; and that is what their madness means. The sane are not a majority; they are mankind. And mankind (as its name would seem to imply) is a kind, not a degree. In so far as the lunatic differs, he differs from all minorities and majorities in kind. The madman who thinks he is a knife cannot go into partnership with the other who thinks he is a fork. There is no trysting place outside reason; there is no inn on those wild roads that are beyond the world.

Eugenics and other Evils (3): The Anarchy from Above

A silent anarchy is eating out our society. I must pause upon the expression; because the true nature of anarchy is mostly misapprehended. It is not in the least necessary that anarchy should be violent; nor is it necessary that it should come from below. A government may grow anarchic as much as a people. The more sentimental sort of Tory uses the word anarchy as a mere term of abuse for rebellion; but he misses a most important intellectual distinction. Rebellion may be wrong and disastrous; but even when rebellion is wrong, it is never anarchy. When it is not self-defence, it is usurpation. It aims at setting up a new rule in place of the old rule. And while it cannot be anarchic in essence (because it has an aim), it certainly cannot be anarchic in method; for men must be organized when they fight; and the discipline in a rebel army has to be as good as the discipline in the royal army. This deep principle of distinction must be clearly kept in mind. Take for the sake of symbolism those two great spiritual stories which, whether we count them myths or mysteries, have so long been the two hinges of all European morals. The Christian who is inclined to sympathize generally with constituted authority will think of rebellion under the image of Satan, the rebel against God. But Satan, though a traitor, was not an anarchist. He claimed the crown of the cosmos; and had he prevailed, would have expected his rebel angels to give up rebelling. On the other hand, the Christian whose sympathies are more generally with just self-defence among the oppressed will think rather of Christ Himself defying the High Priests and scourging the rich traders. But whether or no Christ was (as some say) a Socialist, He most certainly was not an Anarchist. Christ, like Satan, claimed the throne. He set up a new authority against an old authority; but He set it up with positive commandments and a comprehensible scheme. In this light all mediaeval people — indeed, all people until a little while ago — would have judged questions involving revolt. John Ball would have offered to pull down the government because it was a bad government, not because it was a government. Richard II would have blamed Bolingbroke not as a disturber of the peace, but as a usurper. Anarchy, then, in the useful sense of the word, is a thing utterly distinct from any rebellion, right or wrong. It is not necessarily angry; it is not, in its first stages, at least, even necessarily painful. And, as I said before, it is often entirely silent.

Proč jsem katolík

Úvodník v jednom deníku se nedávno věnoval nové Prayer Book, aniž by o ní mohl říct něco zvlášť nového. Věnoval se totiž především tomu, aby po devítisté devadesáté deváté tisící opakoval, že to, co obyčejný Angličan chce, je náboženství bez dogmat (ať už je to cokoliv) a že disputace o církevních věcech jsou plané a neplodné na obou stranách. Jenže jakmile si autor uvědomil, že tímto rovným odsouzením obou stran mohl projevit jakýsi malý ústupek či uznání naší straně, rychle se opravil. Dál totiž uvedl, že je sice špatné být dogmatický, ale zůstává podstatné být dogmaticky protestantský. Naznačil, že běžný Angličan (užitečný to tvor) byl vcelku přesvědčený, že nehledě na jeho aversi vůči všem náboženským odlišnostem, bylo nezbytné, aby se náboženství dál lišilo od katolicismu. Je přesvědčen (tvrdí se nám), že „Británie je tak protestantská jako je moře slané“.

S pohledem uctivě upřeným na protestantismus pana Michaela Arlena nebo pana Noela Cowarda nebo na poslední jazzový taneční večer v Mayfair nás může pokoušet otázka: „Když sůl pozbude chuti, čím bude osolena?“ Jelikož ale z té pasáže můžeme usoudit, že Lord Beaverbrook i pan James Douglas, pan Hannen Swaffer a všichni další jsou pevnými a neústupnými protestanty (a jak víme, protestanté jsou proslulí svým důkladným a rozhodným studiem Písma, v kterém jim nepřekáží ani papež ani kněží), můžeme si dokonce dovolit vyložit toto rčení ve světle méně známého textu. Můžeme se domnívat, že když přirovnali protestantismus k mořské soli, možná jim bleskla hlavou vzdálená vzpomínka na jinou pasáž, v níž ta samá autorita promluvila o jediném a posvátném zdroji živé vody, který dává životodárnou vodu a skutečně hasí lidskou žízeň, kdežto všechna ostatní jezera i kaluže se liší tím, že ti kdo se z nich napijí, budou znovu žíznit. To se občas stává těm, kdo dávají přednost pití slané vody.